From: Muriel Whipple Haddon, Homespun Lore, 1998.

Chapter 3.

GRANDPARENTS

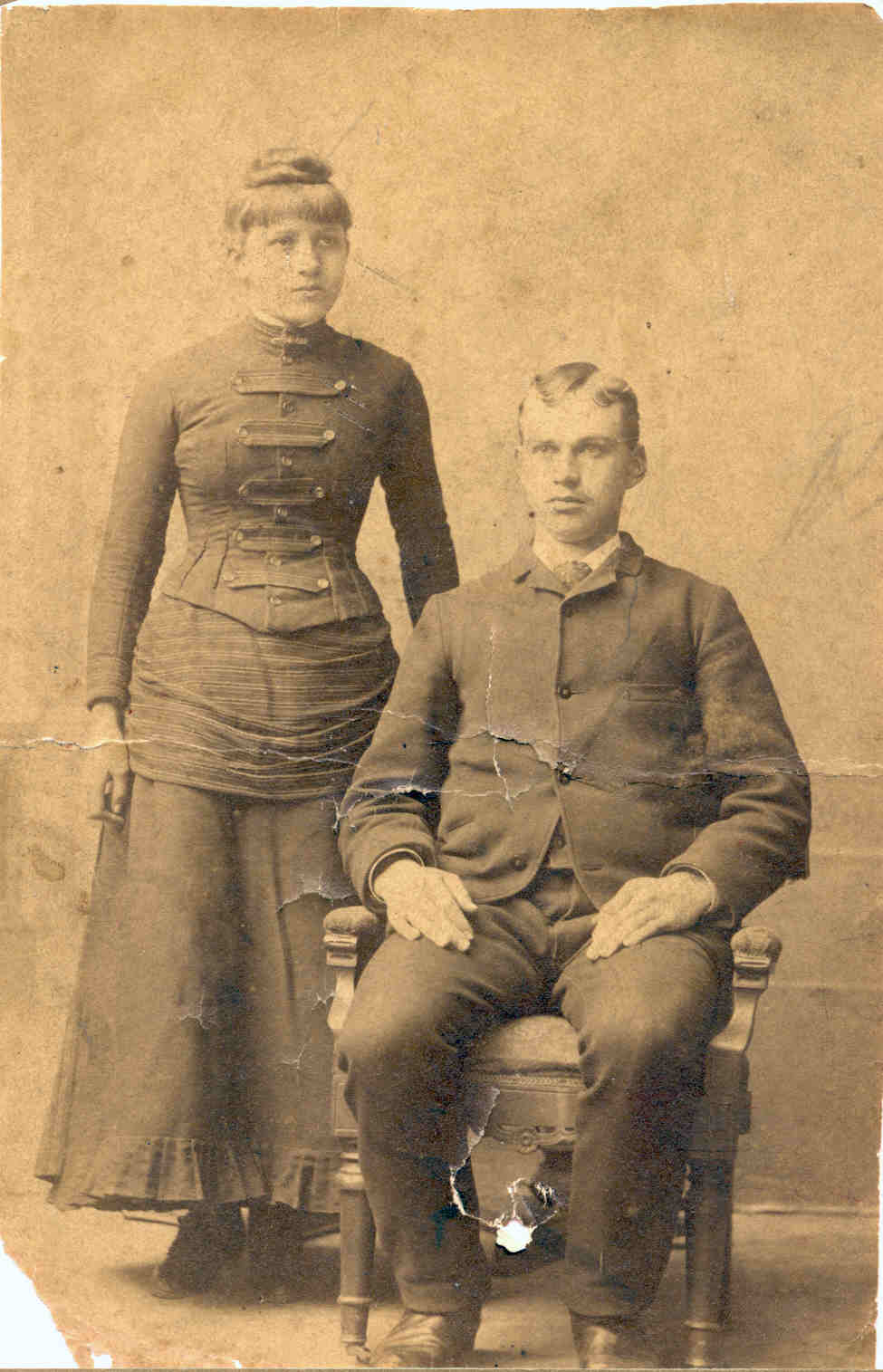

I HAVE OFTEN felt that I missed a great deal by not knowing my grandmother, Augusta Estelle Chapman Crouch. She was rather tall and thin, and her eyes were brown. Her daughter Jessie and grandson Norman are the only ones I know of in the family who have had brown eyes like hers.

Augusta had two sisters, Mary who married Walter Phillips, and Martha who married Joseph Crouch, a brother of her husband Frederick. Two of her brothers, Elias and Elbert, died young. Her mother was Esther Watrous, a rather stern-looking woman. After Esther died, her father, John Chapman, was married three times to women of the Olin family. The first, Isabel, died when a daughter was born who was also named Isabel and who was close to my mother’s age. In fact, they were friends all their lives. Aunt Isabel Clark made visits to our home as long as my mother lived.

Augusta had eleven children. Because of her husband’s work she was often alone with the children. I remember hearing my father say, “My wife’s mother was one of the finest women I have ever known.” My grandmother Augusta had artistic ability which seems to have come in the Chapman line. Great Aunt Mary Phillips began to paint when she was middle aged and had an exhibit in Norwich of her work in oils when she was fifty-five. Two of her children, Roy and Lila, did portraits in oil. Lila taught art a number of years in Norwich Free Academy. She did beautiful work in watercolors, paintings of the seaport in Mystic as well as other scenic areas of Mystic. Lila’s son, Jack Allen, taught art in Willimantic High School many years. Grandma Augusta would draw pictures of animals, cut them out for patterns, put them on cloth, and make stuffed animals for the children. She also taught her daughters how to sew, and Phoebe and Jessie were both considered excellent cooks and were efficient seamstresses. The artistic talent seems to have been passed on to members of the family. My brother Ralph could draw and paint from a small child; Fred’s daughters, Lynn and Chris, are gifted artists; Marjorie, Aunt Jessie’s daughter, has used her artistic ability through the years. My youngest brother, John, developed his talent after he retired, doing beautiful work in both water and oils. He painted a composite of “The Haven,” where he lives in Florida, and it is now hung in the Foresters’ headquarters in Canada.

Grandpa Crouch was a stone mason, and because of his line of work, he was away from home a great deal of the time. He took jobs where he could get them. One time he had come home and, as usual, was very tired. That night my grandmother got out of bed to take care of two crying babies, one of which was sick. She tried to wake her husband to help her, but calling to him had no effect -- he just slept on. At last she put a child at each of his ears, and their loud crying finally woke him.

The family moved often, living in rented houses, which enabled them to be near my grandfather’s work. My mother told me what an enormous task it was to carry out a household move in the winter. The rented houses would be bare. The new tenants were lucky if the place was clean! If not, working with soap and water and mops was the first order of business. The stoves were set up. The pieces of stove pipe often did not fit well together, and a man with cold hands or gloves on would have to work quite awhile to get the pipe together and into the flue. Chimneys were often poor and did not draw well, resulting in smoke pouring into the kitchen until stove pipe and flu warmed up. After the kitchen stove came the parlor stove, with the same procedure repeated. Birds (Chimney Swifts) often built nests in chimneys which clogged air passages, and someone would have to go up onto the roof and push them down into the fireplace. The nests were filled with bed bugs, and many a housewife had to fight these pests if they got into the house. Next came getting the beds into the upstairs rooms. Spool beds were laced with rope and a “tick” filled with straw was the mattress. Today we would call the ticks mattress covers. The beds with springs also had ticks. Straw could often be found in the barn, and the ticks would be filled and sewn up before being placed on the beds. Feather beds were also used. At my grandmother Whipple’s, I slept on both kinds of beds. The spool bed was hard and uncomfortable, but the feather bed was warm and soft.

A kettle, skillet, and enough dishes to eat from for a meal or two were unpacked from boxes. Before nightfall the lamps must be found, unpacked, and filled with kerosene -- there was no electricity. This was about the extent of work for the first day. The next day carpets could be put down in the sitting room and parlor on top of straw which had been brought from the barn and spread over the floors as evenly as possible. But there were always lumps here and there. Ingrain or hand woven carpets were drawn tight against the walls and tacked all around the edge of the rooms. In a year the straw was walked to dust. During spring housecleaning the carpets went onto the clothesline to be beaten, and the floors were cleaned and the carpet relayed over fresh straw . Very few houses in the country had a pump to get water even at the kitchen sink. Water would be drawn up from the well outside by a well sweep or a rope tied to a bucket that was let down into the well. A water pail and dipper provided water at the sink. There would be no glasses and cups by the pail -- everyone drank from the same dipper out of the same pail. How unsanitary! But people did not seem to be sick or get colds any more often than with later sickness preventatives. Uninsulated houses were drafty, insuring plenty of fresh air.

What hard work mothers had to keep the children clean!

Washing clothes took the most of Monday. White clothes were put into a wash

boiler containing soap and water which was placed on top of the stove .

Everything was hung outdoors on clotheslines, winter and summer. Families were

large, and children learned early to do their share of the work.

boiler containing soap and water which was placed on top of the stove .

Everything was hung outdoors on clotheslines, winter and summer. Families were

large, and children learned early to do their share of the work.

My grandmother Augusta was worn out by the time she was fifty. The family had gone to Poquonnoc to the Quakers’ yearly Fourth of July picnic. A shower came up, and she got wet and had a severe cold as a result. She probably had pneumonia. Her sister Mary Phillips had her come to her house at Laurel Hill in Norwich where she was lovingly cared for. But she did not recover. She was buried in Quakertown cemetery beside eight of her children. My oldest brother, Ralph, was one year old when she died, so none of our family knew her.

Only four of the children in my mother’s family grew to adulthood, and one of those, Sylvia, died while a young mother with three children. The following letter, written to Abiah Chapman Phillips, Sylvia’s mother-in-law, shows what a sweet person she was -- also how resigned she was to the will of God. She died in January 1897. Her husband was George Phillips.

September 10, 1896

Dear Mother,

I

am going to try and write you a few lines, you will be pleased to get it. I suppose I could have written before if I

had had ambition enough.

I

think my heart is a little stronger, other ways I can’t see much

improvement. My food does not seem to

do me hardly any good. I have a good

appetite and eat good too, but am about as poor (thin) as May was I think.

George

has not given up looking for me to get better and perhaps the Lord will restore

my health to reward his faith. I feel

entirely contented for the Lord to do his own way for I know that is best. I think George feels so too.

I

often think of Father and hope he is as comfortable as he was.

I

must close now with much love. I feel

that you have done by me all that an own mother could, and I think I love you

just as much.

From

your loving daughter,

Sylvia.

The other three children in the family were elderly when they died. The following poem, written by my mother about her family, graphically tells the story of her mother’s joys and sorrows.

OUR FAMILY

I often wonder why it was

God ever let me live

And why it was that he to me

The breath of life should give.

Our family was large

Eleven children came

To share the same parental love

And bear the family name.

Our home was of the humblest

We had no earthly store

But my father as the saying goes

Kept the old wolf from the door.

The first of all was Sylvia

A blackeyed slender child

Her temper was serene and sweet

And disposition mild.

Next came our little Noyes

Who lived one and twenty days

Then in the quiet church yard

His little form was laid.

The third was Joseph Elmer

His life, too, soon was spent

And to the church yard then again

The lonely parents went.

Soon little John came to them

Their broken hearts to cheer

But he was laid beside the rest

Ere dawned another year.

Willie was the next to come

They thought that he would stay

For he was seven years and past

When God called him away.

Our little Bessie now had grown

To five years old and more

When Jesus took her from our home

To yonder heavenly shore.

It fell my lot to be the seventh

And next our Jessie came

We were constantly together

And always fared the same.

Then came my brother Chauncey

And the Lord let him stay

For he has grown to manhood

And is with us still today.

Now came our little Sydney

The fairest of the lot

His earthly course soon ended

The battle was soon fought.

The last to enter at our home

Was little Margaret

She had such cunning little ways

She soon became our pet.

We guarded her with jealous care

Lest she too fly away

But we found we could not keep her

God would not let her stay.

Before she reached her birthday

When she was five years old

We took her to the church yard

And the funeral bells tolled.

Thru snow drifts we had wearily

Wended our way home

When messengers stood at the door

With sad news they had come.

They told us that our Sylvia

Had passed the valley dim

That thru deaths trying moments

Christ kept her close to Him.

She had grown to be a woman

Now past twenty-five years old

She was married in her girlhood

To a youth both true and bold.

Now the Lord had called her from him

And to leave their children three

Evermore to dwell in heaven

At His own right hand to be.

So the parents broken hearted

Calmly said “Thy will be done”

We too soon shall follow after

When our earthly race is run.

The years they glided swiftly

And my wedding day had come

I must leave the dear old fireside

And my parents humble home.

But too soon there came the tidings

That my mother soon must die

And beside her eight lost darlings

In the church yard she must lie

So with loving hands we laid her

In her last long resting place

Feeling that again in Heaven

We should see our mother’s face.

So now only three are living

Father, too, is growing old

Soon we all will have passed hither

Our life’s story will be told.

We have often been reminded

Of the prayer of mother’s heart

That the Lord could call us faithful

And to none should say “depart”

So to father, brother, sister

Solemn warning I would give

That we constantly be faithful

And for Jesus always live.

(-- Phoebe Crouch Whipple)

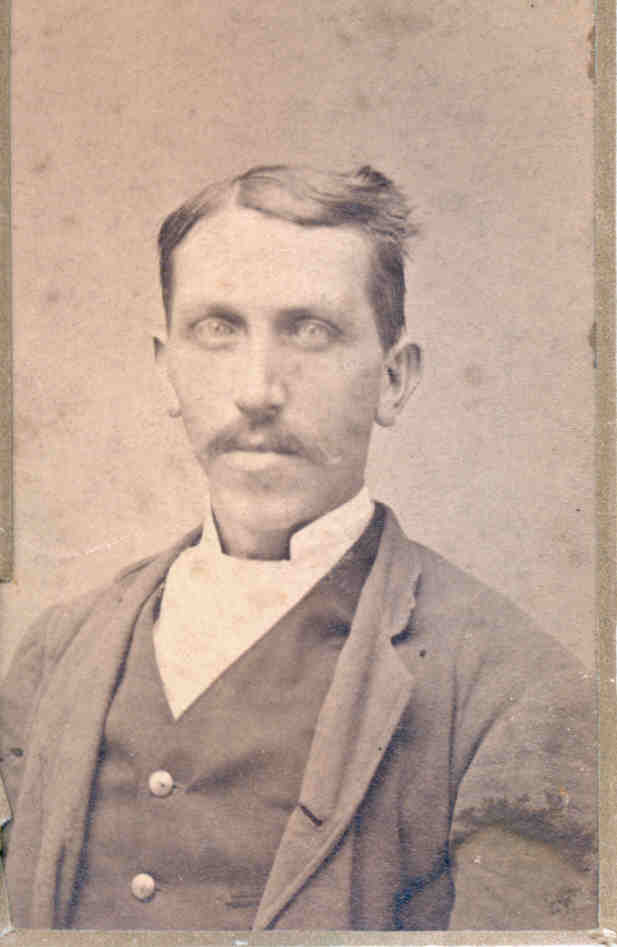

Frederick Nelson Crouch was a real character. He loved people and was sociable and friendly. He never seemed to acquire much of this world’s goods. He never owned a home, to my knowledge, and was always on the move. He was a hard worker, very thorough, whether doing his mason work or tending a garden.

When Grandpa was a little boy, a friend of his, another

little boy, came over to play in his yard. He had a hatchet in his hand and

soon began chopping around in the grass with it.

It was summertime, and both

boys were barefoot. The hatchet boy was getting very near Grandpa’s feet,

saying all the time, “I’ll cut your toe off, I’ll cut your toe off.” Sure

enough, Grandpa looked down and saw a toe in the grass. Quick as he could, he

picked up the toe and ran with it inside the house to his mother. After

disinfecting a needle by holding it over a match, she sewed the toe back onto

her small son’s foot using linen thread, and he was as good as new.

It was summertime, and both

boys were barefoot. The hatchet boy was getting very near Grandpa’s feet,

saying all the time, “I’ll cut your toe off, I’ll cut your toe off.” Sure

enough, Grandpa looked down and saw a toe in the grass. Quick as he could, he

picked up the toe and ran with it inside the house to his mother. After

disinfecting a needle by holding it over a match, she sewed the toe back onto

her small son’s foot using linen thread, and he was as good as new.

My mother told about one day, when she was about sixteen, when she and Jessie had gotten into an argument. Her father stepped into the house just in time to hear her talking heatedly to her sister and mistakenly thought that she was speaking to her mother. He quickly knocked her to the floor, saying, “You don’t talk to your mother like that!” It took a bit of explaining to tell him that she had been speaking to Jessie. He was sorry for his hasty treatment and apologized. Like his mother, Betsy, Fredrick had very decided opinions. Three of his brothers -- Levi, Alden, and Daniel -- seemed even tempered like their father, Timothy. But Fredrick and Joseph, another of his brothers, moved fast.

One summer after Augusta died, Grandpa Crouch was staying with my parents in Quakertown. My father got up at five o’clock in the morning to milk the cows and do other chores. But Grandpa, a very early riser, would announce at breakfast that he had done half a day’s work already. He had started hoeing at three o’clock. By dark, his day was over, and he went to bed with the birds. He believed firmly in Franklin’s adage, “Early to bed and early to rise makes a man healthy, wealthy, and wise.” He seemed healthy and wise, but certainly he never did grow wealthy.

Grandpa used to say my father farmed by the mile. He liked his garden small, and he hoed until there was not a weed to be seen. The last year he lived, while he was staying with our family at Millstone, he had his own little vegetable garden. He was seventy-two and getting feeble. He felt too tired to stand up while he hoed, so he found an old chair and took it to his garden and sat down while he worked. I asked him once why he bothered to hoe when there was not a weed to be seen. He replied, “You have to keep the ground stirred up to keep things growing.” One day a neighbor lady, who could see Grandpa’s garden from her house, phoned us saying, “Your grandfather is lying down in his garden.” I quickly ran across the road over to the garden where I found him lying down hoeing! He said he had gotten too sleepy sitting in the chair. A short time after this, Grandpa didn’t come downstairs in the morning, and we found him still in bed. He said he was too tired to get up. When he got into bed it was August, and he stayed there until he died the next March on St. Patrick’s day. His funeral was one of the last events to take place in the Quakertown Hall. My brother John and I sang together, “The Last Mile Of The Way.”

If I walk in the pathway of duty,

If I work till the close of the day;

I shall see the great King in His beauty,

When I’ve gone the last mile of the way.

Because there was no place left near his wife or children in the old Quakertown cemetery, Grandpa Crouch was buried apart from them in the new part of the cemetery beyond the stone wall. Uncle Levi, his brother, procured a headstone for him and lettered it beautifully.

James Whipple, my paternal grandfather, taught for many years in one room schoolhouses in Ledyard, Connecticut. His reputation was that of being an excellent teacher, and he especially liked literature and poetry. He married one of his pretty, petite scholars, Jeanette Williams, who lived with her parents on Shewville Road in Ledyard. She was sixteen at the time they married, thirteen years younger than James. They made their home with her parents until their oldest son, my father, was three years old. He was called “Alfie.” His first name was James for his father, and his second name was Alfred for Alfred Lord Tennyson. Alfred called his parents James and Jennie until he was quite grown and felt ashamed. After that he didn’t use any names for awhile when he spoke to them directly, until eventually he began to address them as Father and Mother.

During the evenings, from time to time, young men who were preparing to go to college would come to Grandpa to be tutored. Visitors were a rarity, and once, young Alfred, desiring to be sociable, walked up to the boys who had come and announced, “We had mush and milk for supper.” On two successive evenings he repeated this news, “We had mush and milk for supper.” His mother was embarrassed when she heard it the third time and told her son not to tell them that again.

Grandma Whipple said she was twenty years having her four children. The first three were sons, each born roughly five years apart. The second son was named John Samuel after his two grandfathers, John Williams and Samuel Whipple. The third son’s name, Bryant Emerson, was taken from a poet and an essayist, respectively. He never used the poet’s name and was known as Emerson. The fourth child, Evelyn Eugenia, was a beautiful little girl with big expressive eyes and curls like her mother.

If the boys got noisy in the house, their father with a poem in hand would seat the noisy youngster in a straight chair at one end of the kitchen, admonishing him to sit quietly one hour and memorize the poem. John, who was a nervous child, started in his chair at one end of the kitchen, but by the time the hour was up would be at the other end. There certainly was a bonus in this form of discipline -- all the children grew up to love poetry and could recite to the end of their days poems which they had learned in this way.

A snowstorm would often keep Grandpa from going to the store to get presents for his children in time for Christmas Day. The stockings might not be hung by the chimney with care on exactly the twenty-fifth day of December, but whichever day it was, the children raced downstairs in the morning to find candy and an orange in their stockings. Every year Uncle Johnny Williams would give Alfred a new jackknife. The one he had gotten the previous year had always been lost sometime before Christmas. Often in bad weather Grandpa donned what he called his “cloud” -- a big, white, rain-proof covering -- and started out while it was still snowing to walk the two or three miles to Ledyard Center to buy his provisions.

Grandpa Whipple was very interested in the cause of peace. As Vintson Ackley writes,

The Rogerenes have always been active in reform movements. They were among the first to urge openly the abolition of slavery at a time when abolition was not a popular sentiment and those advocating it were often dealt with severely. In the days of the underground railroad Quakertown was one of the stations. Runaway slaves were hidden in the meeting house and were then aided on their way to the next station.

After slavery ceased to be an issue, much attention was given to the cause of international peace. In 1868 the people of Quakertown united with the Universal Peace Union in holding at Mystic the first of the series of yearly meetings which continued for more than forty years. The meetings were held during the latter part of August. The time was increased from one to four days, and the number in attendance increased from forty-three who were present at the first meeting to several thousand who were often present in later years.

Peace Meeting was a big event for the Quakertown people. They drove to Mystic in carriages and wagons to listen to some of the most eloquent speakers of the day lecturing on peace -- William Lloyd Garrison, Theodore Parker, Horace Greeley, and others. Timothy Whipple of Mystic (known as Timmy Whipple by the Quakers) always used to be on hand at the Peace Meeting grove selling ice cream. He was for years a teacher in the town and was one of the most extensive strawberry growers of eastern Connecticut. All the children loved to hear him calling out from his wagon, “Whipple’s ice cream.” They came running with dish and spoon and nickel to get the cold, delicious treat of homemade ice cream. His farm was between Old Mystic (the old folks called it “Head of the River”) and Mystic.

My Grandfather Whipple always attended Peace Meetings and kept himself well informed on the subject. At one time a government headtax, amounting to three dollars a year, was required of all men of voting age. This money was raised to help in time of war. Grandpa refused to pay the tax, and as a result, the authorities put him in jail in Norwich, where he was kept all through the summer. One of his friends visited him there and left with a poem Grandpa had written, which he ended up taking to the office of the Norwich Bulletin. When the poem was published, it caused so much public comment that Grandpa was immediately released.

Thoughts In Jail

By James E. Whipple

I’ve watched the sun slow sinking in the west,

Till he has set beyond yon wooded hills;

Behind those grand old woods where wild birds sing,

And freely flow the waters of the rills.

A few bright clouds above them now are hung,

Like golden islands painted on the sky;

But soon they’ll waste away, like our bright hopes,

Dissolve into the gathering mists and die.

The evening wind comes stealing through the grates,

Through the open grate of my prison cell,

Coming like a loved messenger from home,

With many home sounds that I love so well.

With sounds of fowl, their cackle and their crow,

And bark of dog and stir of grape vine leaves,

And a melodeon’s notes, soft and low,

Comes to me as on many bygone eves.

Now other sounds are borne upon the air.

Like angel tones they fall upon my ear,

Free, joyous shouts from children’s rosy lips,

And a maiden’s song sounding sweet and clear.

Above them all I hear the measured tramp,

Of one, who perhaps, is doomed to wait,

For years in the state’s prison house,

E’re as a freeman he can pass its gate.

Oh! as the poet, Longfellow, has said,

“If half the wealth bestowed on camps and courts

Were given to redeem the human mind from error,

There were no need of arsenals and forts.”

May we yet learn that all of us are linked

With every fellow creature here below;

And that we are judged by the great God above,

According as we lessen human woe.

Text copyright © 1998 by Muriel Whipple Haddon (reprinted with

permission)

Return to QUAKERTOWN Online