From: Muriel Whipple Haddon, Homespun Lore, 1998.

Chapter 2.

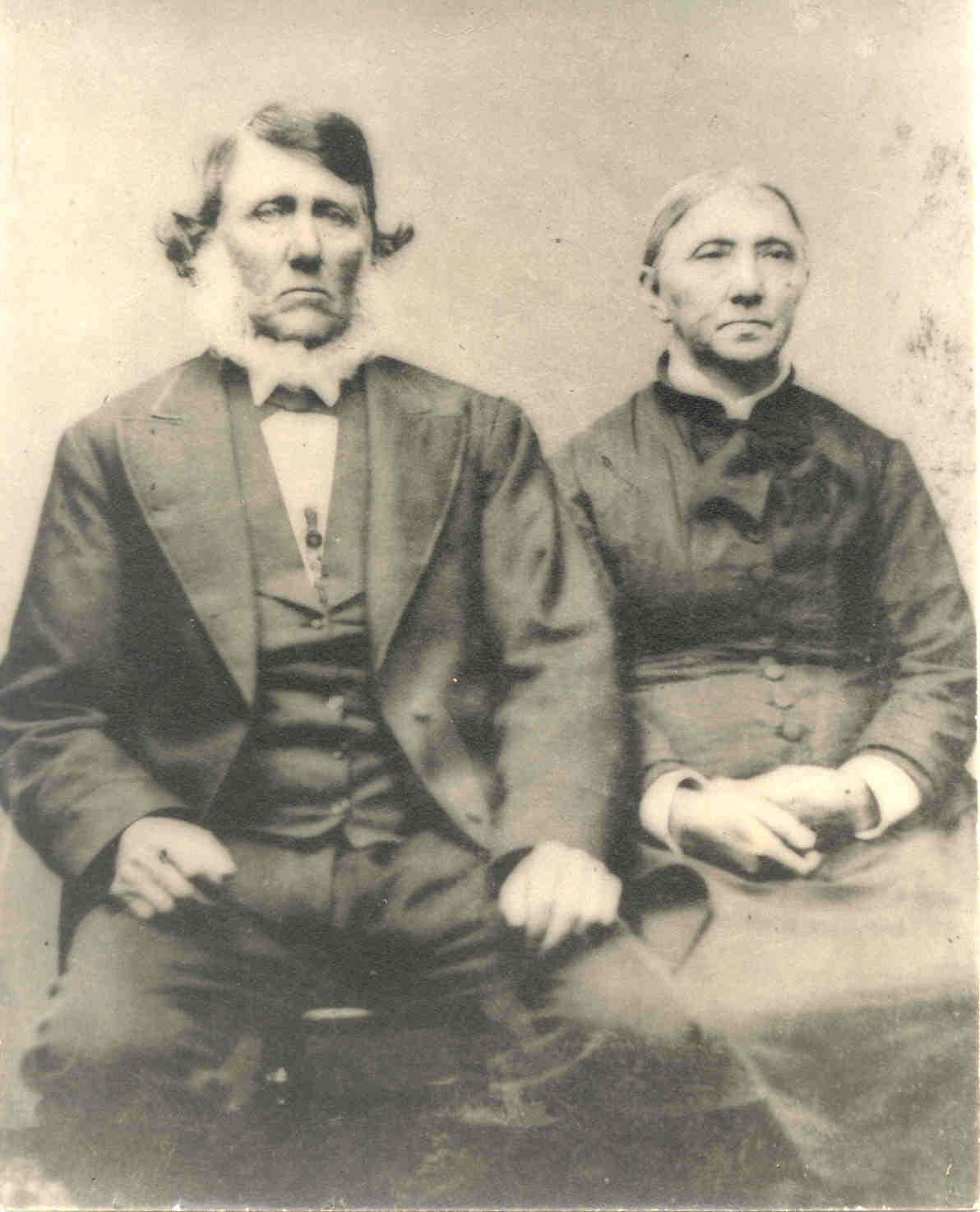

MY FATHER’S AND my mother’s parents were Rogerene Quakers. Well, almost. My father’s mother was a Williams and not Quaker. The children teased my dad at school calling him “Little Quaker,” but his retort was, “I’m half Yankee and half Quaker.” Great-grandfather Samuel Gates Whipple married Elizabeth Watrous. My grandfather, James Whipple, was their son. My mother’s maternal grandparents were Esther Watrous and John Chapman, both Quakers. Her paternal grandparents were Timothy Crouch and Betsy Whipple, also Quakers. If you heard Whipple, Watrous, and Crouch, you immediately connected those names with Quakertown.

The following is a description of Quakertown written by Vintson A. Ackley:

A considerable portion of the southern part of Ledyard is known by the

name of Quakertown. This is in a sense

a misnomer, as the name Quaker has been a term by which the society of Friends

has usually been designated, and the impression has often been given that the

people of Quakertown are a branch of that society. Such is not the fact however, as the settlers of Quakertown and

Quakerhill in Waterford were followers of the teachings of John Rogers, who

lived from 1648-1721 at Quakerhill. He established

an organization which was in the early days known as Rogerenes.

John Rogers was never in any way affiliated with the

Quakers or Friends. He was in his youth

a Congregationalist, but he withdrew from that church and joined the Seventh Day

Baptists. He later drew away from that

church as his own convictions became more established. Some of his beliefs were the same as those

of the Quakers, and it was doubtless on this account that the name became

attached to him and to his followers. But

his teachings were as a whole more similar to those of the Baptists than to

those of the Friends.

Among the early settlers of Quakertown was John

Waterhouse of New London. He located in

Groton in the early part of the eighteenth century. He built his house about a mile north of what is now known as

Burnetts Corners, where he owned a large tract of land. He was an active Rogerene leader and was

succeeded by his son Timothy who is usually known by the shortened name of

Watrous.

Because of the strict religious beliefs and practices of these good people, they were quite careful about not marrying “out.” Once an old Quaker man got up in church and told the assembled congregation, “It has been brought to our attention that our young people are going out b’ twos with outside young people, and we are not going to have it.” As a consequence, many people intermarried, and for several generations there was not much new blood, and many of the people were related.

Whipples and Watrouses were musical. Many of the girls and women played organ or piano beautifully without the benefit of lessons. They played hymns and songs, adding chords and arpeggios by ear. The Watrous and Whipple men were super carpenters as well as good mechanics. The Chapman line had a gift for art. They painted portraits, silhouettes, scenery, and still lifes.

My great-great-grandfather Noah Whipple, with the help of his sons, built two beautiful Congregational churches in New London. Both of these are stone churches with very high steeples. How they put up such structures, without machinery and tools used today, is a marvel. Samuel Gates Whipple, or Great-grandfather Sammy Gates as he was commonly called, told my father stories of how he and his brothers had worked with their father Noah putting up Minot’s lighthouse in Boston harbor. They had to work with the tides, sometimes working all night if the tide was out. They took contracts and stayed away from home weeks at a time. My great-grandmother Betsy, one of the sisters, went along as housekeeper. They would bring a quarter of beef home with them, and it was all eaten by the weekend.

Noah’s first wife, Content, died after the birth of seventeen children. He then married Content’s sister, Christian, who had been married to Daniel Whipple, Noah’s cousin. Christian came to the marriage with ten children. Noah and Christian had five children together, one of whom was the mother of Clara Hammond McGuigan, author of the Whipple genealogy published in 1971. Cousin Clara said she kept a genealogy because she thought a family of thirty-two children was quite unusual.

My father was a good storyteller, and I’ve retold many of the stories he passed along to me.

One story some of the Quakertown boys enjoyed telling was about Charles Plyman Whipple, one of the five born to Noah and Christian. With thirty-two Whipples in the family, the children were often designated as “the seventeen,” “the ten” (who were Christian’s children that came into the family when she married Noah), and “the five.” The story goes that Charles once had a severe toothache. He figured the tooth would have to be pulled, and in his high-pitched voice he said to “the boys,” “I’m not one of your milk and water babies. I’ll not have anything put in my mouth for pain.” But when the dentist started pulling, over went Charles Plyman in a dead faint. The lad who had gone with him to the dentist had fun telling “the boys” how the strong bragging fellow had made out.

Another story I remember hearing was about a Yankee peddler from Preston who came to Quakertown two or three times a year and was welcomed by the farm people. The women did not get to town often. They would buy thread, buttons, and needles to replenish their sewing kits. This peddler drove a horse and wagon and had a stock of all sorts of things: tacks, socks, herbs, vanilla, tea. He made the remark that he had a fear that a tree might fall on him and kill him. On his way home one day a tree did fall on his wagon, and he was killed. The old saying was, “If a man has a fear, that fear will come upon him.”

Jed, a Quaker young man, was in New London visiting at the ferry slip to take him across the river to the Groton side from where he could walk or hitch a ride home to Ledyard. While waiting, he met an acquaintance and was so carried away with their conversation that he forgot momentarily to keep his eye on the boat. Suddenly he realized the ferry was moving. He made a run and a big jump right into the water. No doubt he had quite a long wait in his soaking wet clothes until the next ferry appeared.

It was also Jed who decided he wanted to find out how other people lived. He had only known about his relatives and other folks in Quakertown. In preparation for a trip, he got a pillow slip. In it, along with some other things, he put a dozen hard boiled eggs for his lunch. After boarding the train in New London for Hartford, he threw his ticket into the pillow slip where the eggs were. Soon the conductor came to collect his ticket. After a scramble to find it, he emptied everything in the pillow slip out onto the seat. Eggs went rolling onto the floor in all directions. Once he had found the ticket, it took a little time to get calmed down and restore things to order.

Jed didn't have much of a story to tell even after his great adventure away from home. He told the folks that the people in Hartford slept, ate, and worked just like the rest of us.

My mother went to “meetin’” at the old Hall, as the Quaker church building was called. Families came in carriages, wagons, lumber wagons, and any conveyance they owned. Many in the neighborhood walked. They didn’t worship like the followers of William Penn, although there were similarities. The Rogerene Quakers did not sing, and many of the older ones felt that music was wicked. Individuals would stand as the spirit led and give a testimony or exhortation. One old gentleman said the same thing every Sunday. His testimony was, “I’m always interested (with the emphasis on “rested”) in tryin’ to do right.”

Crippled Aunt Elizabeth Olin, a member of our church, loved children. She had a spotlessly clean bare house. Pots and pans caught leaks from the roof when it rained. Poor as she was, she always brought cookies to church in the big pockets of her apron for the children.

Sunday afternoon was a visiting time for many of the families. After church they would drive over to an uncle’s or an aunt’s house for dinner when the weather was pleasant. Uncle Jeduthan Whipple was good at caring for sick people. He had two houses, one for “everyday” and one for Sunday. Once he took Sammy Gates to his house and nursed him through a severe case of smallpox. Sammy Gates had come home from a job very ill. After the family realized what he had, Lizzie, his wife, vaccinated the family. She had heard all about the new vaccination procedure for small pox. She made a cut on one of their cows, and when the sore became festered she vaccinated herself and the children. None of them came down with the disease.

Lizzie had a great natural intelligence but had attended school for only three days. When her son James, my grandfather, was attending an academy in Rhode Island, he would sit with her evenings working on mathematics. Sometimes they would retire for the night without finding an answer to a difficult problem, and in the morning Lizzie would tell her son that she had thought the answer out in her head during the night. She taught herself to read, and she read the newspapers and “Youth’s Companion” to her husband.

As a boy, my father lived a piece further up the road from Sammy Gates’s place. He told about riding down to his grandpa’s on an errand, just a small boy on a horse. His grandpa came out the door when he drove up and called out in his booming voice, “Lizzie, look! He’s ridin’ just like a gineral... ridin’ just like a gineral!” How proud the little boy felt when he heard those words!

Grandmother Betsy Whipple Crouch, a sister of Sammy Gates, had coal black hair which was black to the day she died in her eighties. Betsy and her first husband, Timothy, had seen part of the United States when they were young. Timothy decided to seek his fortune in the west and took his young family as far away as Iowa where they lived in a log cabin. Times were hard and money was scarce. During the first very hard winter Betsy went outside one day for some wood after having cautioned the children, who were playing, not to go near the fire. Perhaps this put the idea into their minds. Little three-year-old Phoebe Esther got too near the fireplace, and her dress caught on fire. She was burned so badly that she died.

Timothy finally gave up trying to eke out a living in the

desolate country and managed to get enough money together to send Betsy and the

youngest children home to Connecticut on the train.

They arrived home early in the spring. Timothy and the three oldest boys -- Joseph, Frederick, and Levi

-- began walking all the way from Iowa to Connecticut. They ate berries, apples, and the food

offered by farmers along the way. They

were thin, their clothes warn, and their shoes about to fall apart by the time

they reached New York City where a kind man noticed their sad condition and

asked Timothy the cause of the wretchedness.

When he learned that Timothy and his sons had been on the road for

months walking home, he said, “I’m taking you to a restaurant for a good

meal.” He found out they still had to

get to New London and ended up giving them money for the ferry. It was summer by the time they finally

joined the rest of the family in Quakertown.

My Grandfather Frederick told me this story.

They arrived home early in the spring. Timothy and the three oldest boys -- Joseph, Frederick, and Levi

-- began walking all the way from Iowa to Connecticut. They ate berries, apples, and the food

offered by farmers along the way. They

were thin, their clothes warn, and their shoes about to fall apart by the time

they reached New York City where a kind man noticed their sad condition and

asked Timothy the cause of the wretchedness.

When he learned that Timothy and his sons had been on the road for

months walking home, he said, “I’m taking you to a restaurant for a good

meal.” He found out they still had to

get to New London and ended up giving them money for the ferry. It was summer by the time they finally

joined the rest of the family in Quakertown.

My Grandfather Frederick told me this story.

Our Quakers did not have music in the church. My Great-grandmother Betsy thought it was wicked to listen to music. But my mother played the organ her father had bought for her, and Ichabod, Betsy’s second husband, played the flute. My mother’s father, Grandpa Fred Crouch, made a home for his mother Betsy at his place. When Ichabod heard sounds from the organ in the other part of the house he would go, flute in hand, and he and my mother had grand times playing some lively tunes. If Grandmother Betsy happened to be in that part of the house she fled to her own rooms immediately.

After Sammy Gates’s wife died when he was quite elderly, he would “visit ‘round.” When he was visiting his sister Betsy, he often heard Ichabod remark that he “guessed he would leave.” Ichabod spoke often of living elsewhere. Sammy Gates thought fast and talked loud, and he told his brother-in-law in no uncertain words, “I’d go, if I was you, and not keep talkin’ ‘bout it all the time.” But it proved to be only talk. Ichabod stayed on until the end of his days.

Betsy and her brother, Sammy Gates, had similar dispositions. She owned a solid silver spoon, and when she went with the family to eat she looked first thing to see if her spoon was by her plate. If it was not there, she fled again to her own quarters.

I like the following story my mother told about her grandmother (I don’t think Betsy was ever called anything but “Grandmother” by her grandchildren). Betsy’s sister, Aunt Hipsey (Hephzibah was her full name), lived over on Nantucket where she and her husband kept an Inn for many years. One day she came over to New London on the ferry, and a relative took her to visit Betsy in Quakertown. Hipsey thought it would be so nice to have her sister go back to Nantucket to see where she lived and visit the folks there. It took some persuasion because Betsy was no longer in the habit of going very far from home. The two elderly ladies made it to the ferry slip and were about to get onto the boat when Betsy had a sudden change of mind. She said, “Hipsey, I can’t make it.” So back home she went with her carpet bag. She never did visit Nantucket.

At this point I will add a few things of interest about my Grandmother Whipple’s family, the Williams family, who were not Quakers.

Like the Whipples, the Williams family were farmers. They were industrious -- frugal to the point of being what many people might consider “tight.” Be that as it may, they always had money and saved money. I remember my Uncle John (who went as a missionary to India and died there) saying that if he ever had a farm, he would like it to be like his Grandfather John Williams’s place. The picket fences were kept painted white; the buildings were always in excellent repair; the brush was cut, and the grass was trimmed; and flowers and shrubs beautified the property.

After John Williams died, Mary Jane, his wife, kept the house for her son, William Williams. Shortly after the birth of the youngest of his three children, his wife had become mentally ill and could never be home any more. It was good for this family that their grandmother could keep house and care for the children. When the children were grown, Mary Jane’s brother-in-law, Charles Williams, whose wife Maria had died, asked Mary Jane to come and keep house for him. After she had been there for some time, she approached Charles, saying, “Charles, this does not look respectable for us to be living here together. We will have to get married.” He replied that that would be fine with him, so they got married. She showed herself to be a woman far ahead of her time by suggesting marriage herself and even making the proposal to get married. She told me that she had had the two best husbands in the world.

Great-grandmother Mary Jane was a small woman, but well built, and very prim and proper. It was difficult to get a picture of her because she always felt she did not look good enough or was not dressed nicely enough. Once Aunt Nora found her tearing a picture of herself out of one of her albums. When she asked her why she was doing it, she said, “I don’t think I look good.” She always wore a black velvet ribbon around her neck when she dressed up for special occasions. When I was eighteen I played checkers with her several times. She usually won. She was eighty-eight then.

One Christmas at Grandma Whipple’s house we were exchanging gifts, and Great-grandma Mary Jane opened one which turned out to be a piece of cotton material for a shirt waist. When she read the gift card she began to call out to Grandma Whipple, “Jennie, I’ll pay you for it -- I’ll pay you for it.” I was young then and thought it very odd that anyone would expect to pay for their gift. But this was quite typical of the Williams family. They always wanted to pay for everything they had -- and always had the money to do it.

Toward the end of her life, Great-grandma used to sit in a little rocking chair observing activities around her. I remember her watching me wash dishes one day and remarking, “Your mother taught you how to wash dishes, didn’t she?” One morning she was in her little chair and got up, telling Grandma that she felt tired and was going to lie down to rest. In a little while Grandma found her dead in her bed. She was ninety-four years old.

Text copyright © 1998 by Muriel Whipple Haddon (reprinted with

permission)

Return to QUAKERTOWN Online